October 1942

The month of arduous training in the desert was gearing up for something ‘big’. Although the War Diary does not contain any information for the month before 23rd October, Sgt Observer Frederick Sidney Williams personal war diary adds context to what the move from the camp at Almaza to the front was like.

““One fine day we were ordered to pack up. We guessed what for, so we loaded our respective vehicles. I was at that time travelling on Y truck, a three tonner, and after everything was packed there was very little room left for the seven or eight of us who had to ride on it. Early next morning we sailed off, glad to be on the move again – glad to be away from base. We went right through Cairo nose to tail. Through Gezirah over the Mena Bridge and on to the Alex Road, passing two pyramids just beyond Mena, the only two I’ve ever seen.

We saw lots of camps swarming with troops, Egyptian and British, then just the desert on either side of the road. We turned off the road after some twenty odd miles – left – and deployed ourselves into desert formation and travelled for a couple of hours.

It seemed strange when we halted, large expanses of nothing. So, as there was nothing to see, we pitched the bivvies we had been issued with, made ourselves comfortable, fed on meat and veg. And went to bed. Next day we went on again but when we halted that night we could hear a distant rumbling and could see some way off the flashes of guns. We dug our trucks and selves in – it was exciting.

I went off early next day with Mr. Gifford, who had come to meet us, armed with spades and the necessaries to dig ourselves in. We wended our way through narrow gaps in minefields bearing names, all of them, “New Zealand Gate”, “Cannon Gate”, “Hurricane Gap”. All guarded by infantries with fixed bayonets. We drove along sandy stretches, hard and firm, stretching as far as the eye could see. It was a peaceful day and apart from the occasional crack of a 25-pdr, there wasn’t a sound. We passed huge dumps of petrol and ammo; sweating, swearing groups of men going “up”. But generally little activity.

We reached our allotted area at last. It was in a wadi, minefields on two sides, front and left and sandy ridges on the other two. The ridge behind us was “in view” (visible to the enemy). I took good care to keep off it. Breave, when I got there, was busy with a director. Gifford had chosen pivot gun positions, he gave me the griff and then left me with the job of siting and building the command post. I picked a spot between the troops and about two hundred yards in rear, in a small culvert, up against the rear ridge.

Marked it off and three of us began to dig. Shirts off, scorching hot, sweating profusely, digging in fine swirling sand. It came back in as fast as we shovelled it out, so that after two hours solid work, we were exactly nowhere. Heartbreaking. To cap it all the wind began to blow, kicking the sand into our noses, eyes, ears and throats, impossible to work, impossible to see. I lay down, covered my head with my shirt, ached, felt utterly miserable, cursed with greater fervour than I have ever done, almost wept with the feeling of utter defeat. I lay for about an hour when the wind began to ease off for a while, just beginning to resume our work when Wale, the old man, turned up with the Humber, our H truck. He remarked on our slow progress and started off again. The truck dug in the soft sand, we shoved, he sat and swore, eventually the gearbox gave way and Jonah stomped off in a hell of a temper.

Came the morrow, clear again. We got three or four blokes to help us, got some sandbags and began methodically on our C.P. We finished it that day, stuck our three-tonner frame and cover on and moved the boards and stuff in. Not a bad hole. 9 feet long, 7 feet wide and about 4 feet deep.

The guns came in. Joe and Derrick put them in action into the pits which had previously been prepared. We were ready! We only had one assignment here and that was to fire some smoke as if to cover an advance in the hope that the Gerry artillery would open up thus enabling our spotters to “fix” him. Fortunately for us he didn’t open up. But instead the crafty blighter sent over a couple of Stukas.

They screamed down on us and dropped their eggs. Fortunately again, no one was hurt, though the scream of plane and bombs quite definitely upset us. In our place about six of us lay flat with our heads under one chair, silly, but it’s surprising the silly things one does in a hot spot.

We had instructions to prepare to move to a more forward position. I went forward with an H.Q. digging party about seven one evening, 18th of October, I think. The rather humorous incident that cheered us all up was when Bill, driving an old Morris headed straight for a slit trench, it was very hard to keep to the track in the half light. He couldn’t avoid it, so stepped on the gas we leaped the gap, the jolt on the other side shook everyone up in the back. I could hear them muttering.

About ten minutes later, we were very low on petrol and I had to fill her up. Rather a tricky business on the move and I must have spilled nearly a gallon over myself. However, we went on – along a dimly lit “T.T.” (50 div.) trail, for a couple of miles. Finishing up in a shallow wadi, a low ridge in front and behind – the Deif-el-Muhafid Depression.

Our job that night was to build a C.P. There were groups of gunners to dig pits. Captain C. recced a site for me and we, about six of us, set too. His parting words: “For Christ sake, don’t show any lights, he’s only 1,200 yards away”, didn’t serve to cheer us up. We set to, and slaved from 8 p.m. until about 2 a.m., then dropped where we were and slept like logs. Imagine our dismay, when next morning, we found that the hole we had toiled at was in full view of Gerry. Browned off again!

Well swearing wouldn’t do any good, so after a sketchy breakfast, we began again some two hundred yards away. We finished it that day and had most of our stuff transferred from the rear position. The guns came in; we took stock of our area. On the ridge twenty yards in front of the guns was the rear company of Green Howards and a few anti-tank guns – you can imagine how far forward we were. We had orders for the guns to remain silent – obviously something was coming off.”

Diary entry from August 1942 from Sgt Observer Frederick Sidney Williams, 212 Bty, 111 Fd Regt in his family’s memoirs “Our Fred’s War”.

The Second Battle of El-Alamein

23rd October – 4th November 1942

At this point, the 111th Field Regiment had been in Africa for a little over a month. They would soon experience a real Baptism of Fire in one of the biggest battles the British Army faced in the war so far – the Second Battle of El Alamein.

The First Battle of El-Alamein (1st – 27th July 1942) and the Battle of Alam el Halfa (30th August and 5th September 1942) had prevented the Axis forces from advancing further into Egypt and to the Suez Canal, the vital artery that provided a lifeline to the war in the Far East, the rich oil fields of the Middle East, and if captured would likely allow Axis forces to attack the Soviet Union from the south.

Command of the British Eighth Army in North Africa frequently changed, from Alan Cunningham in later 1941, to Neil Ritchie, to Claude Auchinleck, all of which was to the detriment of the morale of the men on 8th Army. Following the First Battle of El-Alamein, Auchinleck wanted to pause and regroup the Eighth Army, which had expended a lot of its strength in halting Rommel, came under intense political pressure from Winston Churchill to strike back immediately. However, he was replaced as Commander-in-Chief Middle-East in August 1942 by General Harold Alexander and as Eighth Army commander by Lieutenant-General William Gott. Gott was killed in an air crash on his way to take up his command and so Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery was appointed in his place.

Lieutenant-General Bernard Law Montgomery, or “Monty” as he was almost immediately dubbed, was at first seen as “just another Commander” in the already long chain of previous commanders. However, Montgomery made a great effort to appear before troops as often as possible, frequently visiting various units and making himself known to the men, often arranging for cigarettes to be distributed. General Harold Alexander was reported to be astonished by the transformation in atmosphere when they visited on 19th August, less than a week after Montgomery had taken command.

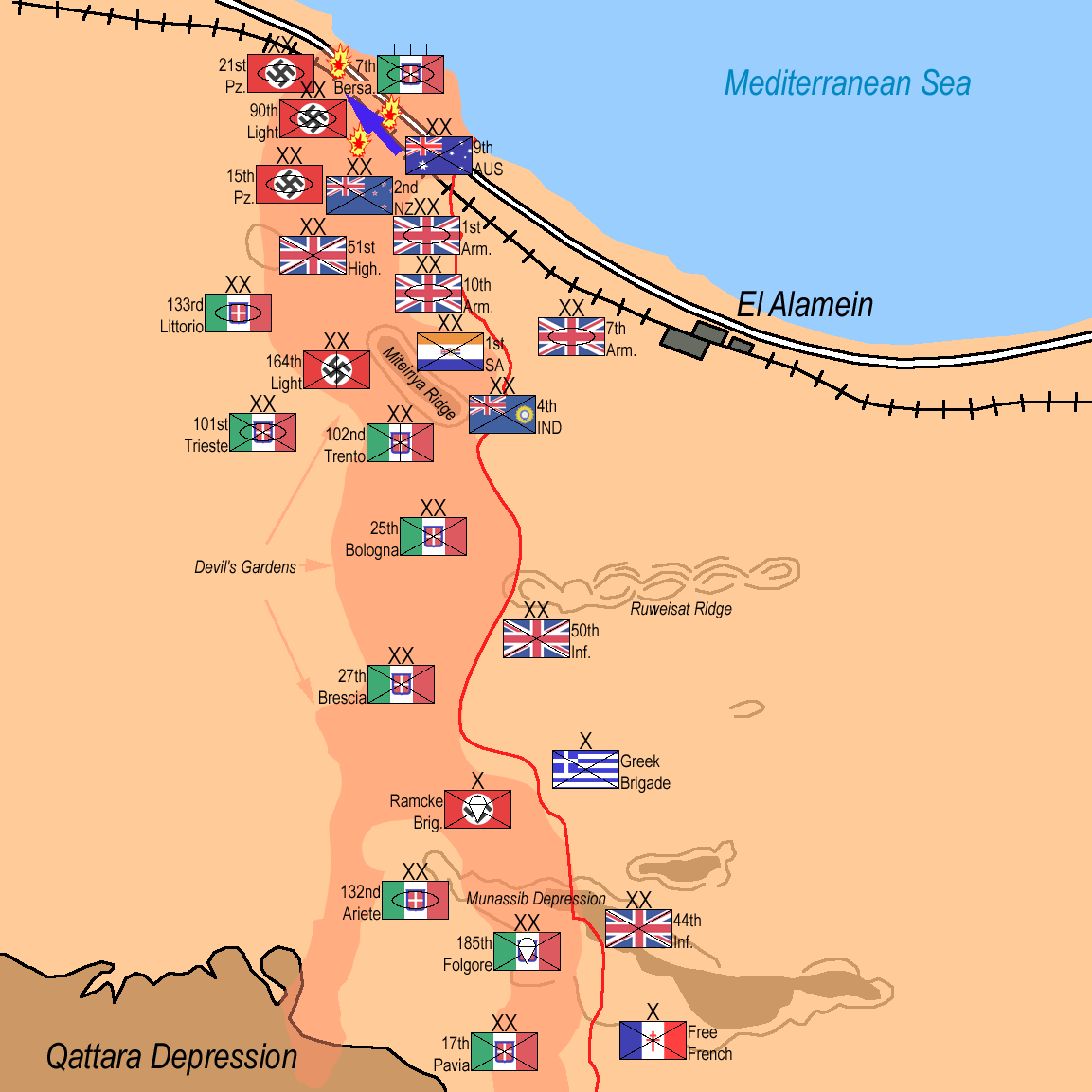

Montgomery had amassed a total of nine Infantry Divisions and two Armoured Divisions, totalling some 200,000 men. This was compared to the Axis forces of two German Armoured Divisions, two Italian Armoured Divisions, two German infantry divisions and six Italian infantry divisions. However, Erwin Rommel (Commander of Germany’s Afrika Korps) was badly outnumbered in armour both in terms of quantity and quality.

Rommel was aware that an allied attack was imminent and had prepared his defences as best he could, sowing hundreds of thousands of antitank and antipersonnel mines (although some reports quote the number as high as 3 million) along his front to slow any allied advance. Rommel nicknamed these defences “The Devil’s gardens”.

To the far south lay the Qattara Depression, an area of some 7,500 square miles containing salt pans, marshes and dunes and impassable to all but light vehicles, meaning that attacks from the southern flank for both sides were not an option.

The 111 Fd Regt were attached to the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, and were located just south of Ruweisat Ridge. Across the minefield in the adjacent Axis lines were the Italian 27th (Bresia) Infantry Division. These battle-hardened troops were no stranger to a fight, having being operational in the desert since 1939 and taking part in the Siege of Tobruk, Battle of Gazala, Mersa Matruh and the First Battle of El-Alamein. The Italians were thoroughly armed, with specialist howitzer artillery pieces, mortar and machine-gun regiments as part of their division.

Operation Lightfoot

The codename for the first phase of the battle was “Operation Lightfoot”, thought to be called because it would be led by the infantry, who would be too light on their feet to trigger anti-tank mines. Montgomery had expected a 12-day battle in three stages: the break-in, the dogfight and the final breaking of the enemy.

The move to the assembly areas was completed on the night of 22-23 October. By first light on 23 October all of the attacking units were in place, dug in and camouflaged, and were able to rest for the day, undetected by the Germans. The main objective was for the northern Allied units to push westwards, with diversionary attacks being carried out in the south to prevent the Axis from reinforcing their northern units.

The following is information directly from Divisional Order No. 19 which laid out the plans for 50 Division (including 111 Fd Regt) parts in Operation Lightfoot. Only information relating to 111 Fd Regt has been included.

At 21:40hrs on 23rd October 1942, over 800 artillery guns along a 40 mile front began their bombardment of the enemy lines, and over the next five and a half hours each gun would have fired over 600 round each (529,000 shells in total).

British engineers, followed by infantry and tanks, advanced to clear paths through the minefields. Although the Axis commanders were taken aback at the violence of the assault, the Eighth Army’s progress was painfully slow, the British Armor failing to get to grips with the enemy. Rommel, meanwhile, mounted spirited counterattacks

““It was as I turned that all Hell seemed to be let loose. The sand beneath me quivered and, overhead, express trains seemed to be whooshing through the air. I looked back and there, on the horizon, vivid red gun flashed stabbed the sky. In, out! In, out! For miles they stretched in either direction, the shells bursting from the guns in a warm arc of light. Our barrage had opened up. It was frightening, coming so suddenly after the eerie silence. Never had I heard or seen anything like this. I could actually feel the noise being conveyed in waves beneath the ground, which was moving every so slightly up and down. “I wouldn’t like to be on the receiving end of that lot,” I muttered to myself, as I pictured all these shells pounding the enemy lines.

Suddenly came a command from our officer. “On your feet!” he shouted, and to right, left and in front of me, I could see dim shapes scrambling up. “Well, this is it,” I murmured to myself. My initiation into war was about to begin. The offensive had started. We were going in!”

Harold Moon’s recollection of the opening barrage at El-Alamein, from his entry to the BBC’s “WW2 – Peoples War” project. Link

““My God! What a night, as if all hell had been let loose. An intensely quiet day – and then at nine-thirty the whole earth trembled and seemed on fire. I was too excited to sleep. No one knew exactly what was going to happen, except that it was something big. I sat on a hillock behind the C.P. and saw the flash of guns for miles. The previous day we had been mortared and a complete gun sub put out of action, so one or two of the blokes went on the gun. I didn’t, having worked long enough.

About ten o’clock things got really going and the chatter of machine guns and rifles mingling with the roar of 25-pdrs and 4.5 inch medium field guns was nerve-wracking. My prayers were all for the P.B.I (Poor Bloody Infantry).

In the very early morning Wale woke me up, we had an urgent call for smoke, some infantry were in a hole. Partington and I worked like slaves to get it out; we didn’t bother to waken anyone else, no time anyway. The OP wireless went off. We found later they had had a couple of mortars all to themselves. Harries, Welsh schoolboy rugby international and a pal of mine had both his legs blown off. Another bloke killed, two seriously wounded, poor old Neden, a nervous wreck, Captain Miller taken prisoner, he later escaped in the back of a Sherman. What a bloody night.

Next day, the battle still raged, we were bombed and another bloke killed. We had to make a jildi (hurried) move to another sector.”

Diary entry from 23rd October 1942 from Sgt Observer Frederick Sidney Williams, 212 Bty, 111 Fd Regt in his family’s memoirs “Our Fred’s War”.

| 24th October 1942 – Field, south of El Alamein |

|---|

| 08:10hrs – Casualty report from 212 battery. Killed in action -3. Wounded and evacuated – 1. Superficially wounded – 2. Captain K. W. Mellor R.A. suspected wounded and missing. |

| 13:00hrs – Captain Mellor reported safe having been prisoner in Italian hands and escaped |

| 15:45hrs – Regiment fired 432 rounds on 300 MET and Tanks in ALINDA DEPRESSION. Result cannot be seen from R3. |

| 15:46hrs – 476 Battery under mortar fire |

| 22:30hrs – 124 Field Regt. Group (111 and 124) fired concentrations for 80 minutes on areas in squares 878 259, 879 259, 878 258, 879 258. |

| 24:00hrs – A very quiet day for the regiment, Infantry held up and an enormous battle in progress 879259 and 880259 which was broken off at nightfall. The battle could be seen from all O.Ps and also 476 Bty gun position. |

| 25th October 1942 – Field, south of El Alamein |

|---|

| 11:25hrs – 212 battery bombed. 1 O.R. killed. Armoured division advanced during the day to 880260 and then withdrew. F.O.O from 476 Bty supported. |

| 23:00hrs – 111 Fd Regt supported attacks by 6th Green Howards on Points 92 and 94 882261, and S. E. Yorks on Pt. 101 880261. A smoke screen was formed to cover F.U.P (forming-up place). Concentrations fired. F.O.O’s from 212 and 476 with infantry. |

| 26th October 1942 – Field, south of El Alamein |

|---|

| 00:42hrs – Pt. 94 taken. S. E. Yorks held up. |

| 00:55hrs – 111 Fd Regt put down concentration on Pt. 101 to enable S.E. Yorks to withdraw. |

| 02:23hrs – Concentration fired west of Pt. 92 but 6 Green Howards were held up by heavy enemy artillery fire. |

| 06:46hrs – C.B. (Counter Battery) fire against two enemy troops. |

| 08:45hrs – S. E. Yorks and F.O.O from 212 Bty returned to F.U.P. |

| 14:35hrs – Concentration fired on Pt. 92 in preparation for 6 Green Howards fresh assault. |

| 15:15hrs – Observed fire from 476 Bty on Pt. 92 causing heavy enemy casualties but forced 6 Green Howards to retire to Pt. 94. |

| 27th October 1942 – Field, south of El Alamein |

|---|

| 07:55hrs – Warning order for Regt to move north. |

| 14:00hrs – RHQ (Regimental Headquarters), 211 and 212 Btys moved to area 882275 to support 1 Free French. 476 Bty under command of 124 Field Regt Group. |

| 28th October 1942 – Field, south of El Alamein |

|---|

| 08:40hrs – 212 Bty shelled. 1 O.R. killed. |

| 10:10hrs – RHQ shelled. 1.15 art destroyed. |

| 18:00hrs – RHQ moved to 8841 2751 |

“We took over at night from the 1st field in the “New Zealand Box”, Central section, supporting Greeks and Free French. Our front was very thinly held, and to baffle the enemy our transport ran up and down behind us for a couple of days to make him think we were stronger than we actually were. We supported Greek patrols and then after ten days heavy fighting, we heard they had broken though in the north.””

Diary entry from 23rd October 1942 from Sgt Observer Frederick Sidney Williams, 212 Bty, 111 Fd Regt in his family’s memoirs “Our Fred’s War”.

| 29th October 1942 – Field, south of El Alamein |

|---|

| No change in general situation. Targets engaged as observed. |

| 30th October 1942 – Field, south of El Alamein |

|---|

| 13:00hrs – 476 Bty came under command of 74 Fd Regt. 1 O.R. seriously wounded. |

| 21:00hrs – Engaged enemy with harassing fire from temporary position until 0600 hrs 31 Oct |

| 31st October 1942 – Field, south of El Alamein |

|---|

| 22-00hrs – 211 Bty engaged enemy with harassing fire from temporary position |